She Encounters a Sorcerer

When she was a small child playing by herself in the Beijing courtyard she thought that if you dug a very very deep hole all the way to the other side of the globe, and crawled down, you’d find yourself eventually crawling up into a land where everything was upside down. Whatever was true at the start of your hole would be not so at the end. Up would be down. Black would be white. Bad would be good.

Several decades later the paradise she sought on the northern California coast had turned into hell. Her young son had left her to live with his father saying “I don’t want to live with drugged out women.” Her daughter had run away from home before that. The woman she was in love with, had gone to live with another woman she was in love with. Finally, Bob, with whom she seemed to have a future, was lost at sea while fishing. Her heart was way beyond repair. She had only a dog to make arrangements for and she left him with her dear friend, Nancy.

Standing on a rock above the pounding waves in a full moon, she chopped off her long hair, so long she had to be careful not to sit on it in the toilet , and tossed it all, long strands of black hair along with her entangled past into the roiling black sea.

Freedom’s just another word for nothing more to lose…

wailed Janice Joplin.The I Ching advised:

It furthers one to cross the great water.

She crawled through the hole back to where she had come from. There she met Lin Yun.

The airplane descended between green mountain peaks, banked sharply, dropped, it seemed, below the level of Hong Kong’s skyscrappers to where you could almost scan the billboards and roared to a landing. The airport bus headed for Tsim Sha Tsui careening through the narrow teeming streets of Kowloon. From its window I suddenly spotted C.Y., a tall young film director I had met in Taipei a few days ago. As the bus lurched noisily around the corner, I slid the window open and called his name. Our eyes met. He had just enough time to yell back “Hotel Fortuna!” Standing next to C.Y. had been a short, portly, moon faced, middle-aged man in a grey suit–a split second first sighting of a most important person in my life by the slimmest of chances.

At dinner that night C.Y. introduced me to Lin Yin and their other friends. After that I never saw C.Y. again, but I was drawn immediately into Lin Yun’s circle. Many afternoons we gathered in the lobby of the Peninsula Hotel, an elegantly appointed colonial landmark on the Kowloon waterfront. Under its high ceiling we sipped tea or coffee as trays of French pastries were wheeled around its marble columns. Boys in Philip Morris uniforms paged the lobby holding above their heads long sticks with name cards of those receiving phone calls. They announced themselves with little tinkling silver bells. If you spotted your name and you wanted to take the call, you nodded and a phone was brought to the table on a silver plate. There was nothing that could not be done from the lobby of the Peninsula. It was the kind of place where you would not be surprised to see Sidney Greenstreet biting into a Napoleon or Peter Lorre lurking behind a potted plant, or a certain Chinese psychic surrounded by an eclectic following.

Lin Yun was a professor at Yale-in-China where he taught Mandarin as well as Chinese history and culture, including the I Ching and Feng Shui, mostly to foreigners. I noticed that people often asked him for advice. They seemed to think that he saw what others did not.

His group of regulars was as curious about me as I was about them. To them I was an overseas Chinese returned home, an exotic hippie in funky patched clothes, daughter of a famous and much respected scholar and political dissident on Taiwan. To me they were the first Chinese friends I had as an adult, Mandarin speakers, sophisticated, witty, conversant in spiritual concepts as well as world affairs. Among them was a lesbian singer, a beautiful young actress who was the granddaughter of a close friend of my father’s, her boyfriend, a cute matinee idol, an avant guard abstract oil painter, a wealthy jeweler, a dermatologist. My ears were open in intense learning mode; my Chinese, faded from some thirty years of neglect in the states, was slowly coming back to me.

From the Peninsula we would move on to one of Hong Kong’s incredible restaurants with the jeweler or dermatologist picking up the tab. One night we were around a large round table devouring seafood and talking of qi (vital energy) and how one’s qi leads one upon the right path. “There,” Lin Yun directed an amused look at me. “Is someone who has been walking the wrong path for ten years.” The table broke out laughing. I was stunned and had no come back.

L. L. a famous film actress then living in LA ,stepped into the breach. She was in HK to play the Empress Dowager in an epic historical movie. She said she could not sleep in the cottage assigned to her, would Lin Yun help. In the small hours of the morning we all piled into cabs and went out to her cottage on the backlot of Shaw Brothers Studios and moved furniture under Lin Yun’s direction. This was Feng Shui a la Lin Yun, a grand master of the Black Sect of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism.

The remark about my being on the wrong path for the last ten years stuck with me. I amused myself with l’esprit de l’escalier “If I hadn’t been on the wrong path, how could I have met you?” However, I did realize that it had been an invitation for me to ask him about my qi, an offer for a reading. He was in great demand as a qi reader, a fortune teller. I was not, at all, adverse to consulting fortune tellers, in fact I often sought them out, but, for some reason or other, I did not take the bait.

In those days I was staying in the storage room of some friends’ apartment. About 2 o’clock one morning they called me from my sleep to answer the phone. It was Lin Yun. “Can you come out?” I was surprised; we usually agreed on where to meet the night before; I didn’t think he even knew my phone number. I called a cab and met him in the lobby of a hotel where he was waiting–alone. I had never met him alone. We performed the ritual of the red envelope. All those who sought to consult him must present him with a red envelope; he took the envelope and returned the money inside. He slept with all the red envelopes of the day under his pillow. It was a gesture that placed the responsibility of the advice with the seeker; he did not offer advice; he only gave it when asked. The red envelopes under his pillow protected him from absorbing others’ bad qi.

He was very serious and spoke softly but bluntly. He said he could see from my qi that I would be considering suicide within a few days. Surprised, I told him he could not be more wrong. It was true that I had been depressed in California, but since coming to Hong Kong, my mood had lifted. I was having a wonderful time. He persisted with his dire prediction. He said gently that my qi was shooting out to the sides rather than straight up as proper qi should. In his view I was not out of trouble, but stumbling blindly toward disaster. Never for a moment did I believe him.

A few days later came another late night phone call; this time, from San Francisco. Tom’s voice said “I hope you’re with people who love you,” then went on to deliver the news that shattered me. “Didi died in a car crash today”. She had had a collision with a truck.

I called Lin Yun. He came immediately. I asked him if he had done this, if he had caused Didi’s death. No, he said quietly and matter of factly; he did not have such powers. I talked to him a little about Didi, about our ecstatic but often tortuous relationship, the woman I had been in love with for the last several years. Because our spirits were entwined, he said, I would be tempted to follow her. I no longer doubted his words. He had brought some small bananas and a red cord. He performed a secret ritual to separate our spirits and to send her peacefully on her way. He talked to me then about my children and how suicide was often passed on in families. Parental suicide inflicts profound damage to the qi’s of the children.

All I wanted to do was to be left alone in my windowless storage room. But Lin Yun insisted on my staying with him on his busy social rounds. I was beyond resistance. He came for me each morning and delivered me late at night. So I walked, like a zombie, on the busy streets of Kowloon with tears rolling down my face. I followed him in a daze from crowded hotel lobbies to restaurants to bars. Lin Yun said to his companions, “This is my friend Yeh Tung; she’s lost someone she loves”. People were kind but not overly solicitous, and asked no questions. It was, in an unexpected way, strangely passable.

Night followed day; day followed night; a week or two passed. We were in a bar sitting around a dance floor. A Filipino band was playing. He asked me to dance with him which seemed peculiar at the time because he did not know how to dance. However, I got up and began to show him where to place his hands on me. The band segued into a Latin tune that sounded vaguely familiar. We began to move in a basic rhumba box. The singer sang into the mike, “Corazon de melon, De melon melon melon….” It was a little Spanish ditty that Didi used to sing to me in Mendocino in the tiny cabin we had built together.

I froze; I could not believe this. I explained to Lin Yun. Heart of melon, melon, melon… He smiled and did not seem the least bit surprised. He continued to move, pushing and pulling me along: one two three hold five six seven hold one two three hold…. Corazon de melon, de melon melon melon, Corazon….

Lin Yun was becoming increasingly famous; he was hot, gaining a large number of followers, and quickly becoming a Hong Kong celebrity. In that year I too had made advances in my career, often with his help, magically with his rituals and in more mundane ways with his introductions to influential people. I began to work regularly for television making documentaries. This was the very first job that really used my talents.

Nationalist enough to not want to serve the Brits, I chose to work in the Chinese branch of the station. This made my job twenty fold harder. Communicating in my halting Mandarin would have been difficult enough, but in Hong Kong Cantonese was the local dialect. My Cantonese was a big joke; simple phone calls turned into muddled humiliations. Another difficulty was trying to hide the obvious fact that I could not read or write Chinese. On top of all the language barriers, there were my technical inadequacies; in a booth with eight TV screens, levers, and buttons, and joy sticks, mikes to the narrator on the stage below, to the telecini, to the audio controller, I froze. Overcoming these obstacles consumed me. This was the right path?

It became more difficult to meet. The entire group was moving ahead, each in a different direction. Lin Yun called himself a charlatan, denied having any particular powers yet people fought to get their qi read by this Master of the obscure Black Sect of Tibetan Buddhism. He was now surrounded by a different sort of people, not friends but followers, groupies, guru worshippers, who fought to touch him, who broke into his apartment and hid under his bed. It was the beginning of a cult. His old friends felt slighted and annoyed. He was often away; whenever anyone sent him an airplane ticket for him to bless their house or business, he went (he loved to fly)—to Taipei or Singapore or Sidney wherever the Chinese diaspora had spread.

His feng shui rituals were making people rich. Not me. Even as I became a rather well known TV producer, I did not make enough money to move out of the storage room of my friends. I did not know how to ask for a raise. “Lin Yun, will I ever be rich?” I asked him lightly one day.

“No. You will never be rich.”

“Why not?”

“You will never be rich because you don’t mind being poor. When have you ever given a thought to making money?”

Walking past a beggar, “Lin Yun,” I asked him. “Why do you make the rich richer, but give no help to those who really need it?”

“I only help those who ask for help,” he explained, rather patiently, I thought. After all, I knew about the meaning of the red envelope ritual; Buddhists did not proselytize. Then he gave me a look. “You are no better than anyone else.” His remark, gently enunciated, busted me. It wrenched me out of my self righteousness. He had not ever spoken in this way to me before; he seemed to be opening a new door. There was a moment when I could have gone through and taken some steps upon a different path, but I did not. It was all too serious. I did not accept his offer of help in the earnest pursuit of awareness, of self knowledge. My armor cracked but I kind of just went on my befuddled way. What would my life be today if I had taken that other path?

I returned to California. Failing to find a job in Hollywood, I bought a yellow Plymouth convertible, an old slant six, and headed north to San Francisco. As I had to pass through the San Fernando Valley, I visited Lin Yun’s sister. I knew he’d be there, having only recently arrived from Hong Kong. He was as exhilarated as I was to meet him on this side of the globe. I showed him my new old car and told him I was on my way up the coast. As it happened, he was going there too and wanted to go with me in my new yellow convertible. “Come on then!”

Big Sister’s house was filled with his followers, milling about, useless and out of place. Big sister was calmly fixing lunch in the kitchen for her four teenage kids. When the followers got wind of what was happening they all asked to come along.

“No!” I thundered, rude as rude could be. I jumped in the convertible and he followed quickly, no packing, no goodbyes. We screeched onto the freeway ramp in a mad dash for freedom. Leaning around the turn I glanced over at him and saw beneath his wind whipped hair, a gleam in his eyes. But his lips, I thought, betrayed a wavering hesitancy, a fear.

This was America. This was Hollywood. He entertained neon fantasies of the Playboy Club, he imagined himself surrounded by pretty starlets. He wanted to escape with me in my yellow submarine. But, I read from that brief expression that passed over his lips that he was bound deeply by strictures, encumbered by the mandates of his Buddhist teachers as well as his own often repeated vows to be of service to all sentient beings. He was not supposed to have a “self” let alone “desires” for a voluptuarial life.

Traffic was intense—rush hour. We were in one of the left lanes edging past eighty. I identified one blue car chasing us but still some distance behind. “Look behind us,” I yelled against the wind and the roar of traffic. I signaled with my arm, stepped on the gas, veered left another lane and passed the car in front of us.

He named the occupants of the blue car in pursuit. The wind took his words away. “Three!…” He held up three fingers. “Three cars.” No more hesitancy; he was grinning with the thrill of the chase. “Faster!” cried the Grand Master of the Black Sect of Tantric Buddhism. I located all three pursuers in my rear view mirrors and kept track of their movements as I tried to widen my lead by passing another car on the right. But, alas, my old slant six was no match for these souped up LA sports cars. Behind us the dreaded dreadful followers were gaining.

“Get off the freeway,” Lin Yun shouted. He pulled himself up into standing, the fierce rush of air distorting his face, and pointed right to the ramp. We were much too close to cut suddenly across the three lanes of dense traffic. “Now!” No way. “Turn! You can do it!” he yelled.

I didn’t. I kept the Plymouth in my lane. The exit passed. The opportunity zipped by. “We would have been killed,” I protested.

“You have no faith.”

True. I did not think we could levitate across three lanes of traffic. He said no more. Nor did I. Somehow our pursuers disappeared. I didn’t even know when, so focused was I with the rift between us. Once more he had taken me to the edge; once more I had failed him. I remained a superficial dilettante in the world of magic.

Lin Yun slept all the rest of the way to San Francisco.

The next thirty years passed with our meeting only occasionally.

He bought a large mansion in the Claremont district of Berkeley not more than twenty minutes from where I lived. He established a temple there.

On the few times that I came to Yunshi Temple I was always delighted to see him and he never allowed me to leave without the reassurance the feeling was mutual. A couple of times we met in other venues, for the lunar new year, or for his birthday which was shortly after the new year and usually celebrated together, along with heavy fund raising in some enormous fancy restaurant. Once I happened to be at the San Francisco Airport, coming or going I can’t remember, and walked by one of these and crashed it.

He was singing a popular Taiwan song karaoke. I remained on Yunshi Temple’s mailing list, but it was not what it used to be.

Yet he was the one I called when my father died; again when my mother died.

He came to an exhibition of my family’s art collection at the Asian Museum. As he was a passionate scholar of Chinese art history, he was very excited about the scrolls and from his wheelchair was able to recite many of the poems. He greatly enrich my understanding of the collection.

I remember he read the qi of one Ming Dynasty poet from his calligraphy: the way he had left one character dangling by itself in the last line suggested to Lin Yun that he had a tendency toward suicide by hanging. Indeed that was how the poet’s life had ended. I thought perhaps Lin Yun already knew that. I did not ask him, choosing, once more, to be a skeptic.

When he was pushed in front of a large lotus painted for my father by Zhang Daqian, Lin Yun asked to be wheeled closer and identified a small bent bud in the lower right corner as the most significant part of the enormous scroll. It symbolized my father, he said, under heavy political oppression.

In front of one of the last calligraphies done by my father of a famous poem by Du Fu written in the eighth century in midst of a civil war when he was stranded far from his family, a situation similar to my father’s, Lin Yun recited, by heart (he was too far to be able to read the grass style calligraphy) , the sad lines:

The nation destroyed , mountains and rivers remain.

The city in spring; grass and trees grow in wild profusion.

My tears of grief water the flowers.

Despising separation, even birds scattering from trees shatter my heart.

Beacon fires have burned for three long months now.

A letter from home is worth ten thousand pieces of gold.

Scratched thin, my white hairs can no longer hold a hairpin.

The last time I saw him was in the hospital. His whereabouts and the seriousness of his condition were carefully guarded secrets. My friend Deborah Gee, one of his inner circle, had picked me up and driven me to see him for a final visit.

I paused at the half open door. His eyes were closed, mouth open, breathing labored. Tubes were dripping, monitors radiated a green glow. I waited by his bed. When he came to he seemed to know me but was thrown back to our Hong Kong days and spoke to me as though no time had passed. He asked after my father who had been long dead. After a while he joked, rather surprisingly, “I’m glad you came: now I’m not the oldest person in the room.” Relieved at his levity, I shot back that he was still older than me by a number of months unless he had a transcendental method of reversing time.

The room was crowded with his disciples many of them mumbling prayers. In the hallway there were more followers waiting to get in. C., who had been managing the temple, was trying to get him to eat some chicken soup and he really didn’t want any. She was raising his head and trying to spoon it into his mouth. He was in no condition to eat and kept saying “No more, no more…” until he threw up. I felt anger rising in me but kept my mouth shut. I remembered his words, “You are no better than anyone else.”

One of his followers crowding the hall outside held boxes of sweets. Sweets!!! For a diabetic! Ignorant! Again I took refuge in superiority. Later I was introduced to the woman with the pink cake box; she turned out to be a nurse. The sweets had been for the others. “You are no better than anyone else.”

He seemed resigned to the efforts of his disciples and the medical staff to keep him alive.

Modern medicine! Now my head rang with strident opinions on end of life choices and my own desire to die naturally without entubations, drugs, or other devices to extend the quantity but not the quality of life. My own living will had been signed and notarized with copies hanging on the kitchen refrigerator, in my medical charts, hospital records… Here he was with multiple endstage diseases that he hoped would release him from his suffering, but he was not allowed to leave. He was once more, I thought, a prisoner, of his followers.

A couple of years before he had confided to me that he had been so happy when the doctor had told him of this heart condition as he thought he had a chance at a quick exit. But then he was prescribed some pill which C. made sure he took each day.

He had wanted to die on Chinese soil; they had moved him to the temple in Taipei. But as his condition worsened, they panicked. As he burned with inexplicable fevers, they dragged him back here to consult with American specialists, then back to Taipei, then here once more to see more specialists, surgeries, treatments. His life was not his own. It had not been since he had been “chosen”.

He had been “picked” by an old monk. It was his Big Sister who had been studying Buddhism with the Grand Master. One day the venerable one had been at the bus stop waiting for her to arrive for a lesson when he spotted Lin Yun on the bus next to her. ( I am reminded of the way that Lin Yun had first seen me on the bus from KaiTak Airport.) The old man knew at once that this was the boy to whom he was to transmit his teachings. Lin Yun was about six, and deeply resented being forced to study while others played. He spent most of his time challenging the views of his teacher, devouring sutras and doctrine and texts in order to hold his own against the old man, and that was how he had learned Buddhism.

When I was told he had died, I felt nothing. I had been waiting for that phone call ever since I saw him a few weeks before in the hospital. Now that it had happened I felt nothing but a vague guilt at feeling nothing.

Tibetan Buddhist funeral rites, particularly for Grand Masters, are lengthy, baroque, arcane, and repeated over and over again, at prescribed intervals at various locations and finally, in a grand finale at the burial site. After that another prescribed schedule of ceremonies followed.

The one I was able to attend was a few days after his death and at the second Berkeley Temple where he often gave workshops. The congregation of so many people in such profound grief was overwhelming. I wandered around and finally settled in a folding chair just behind Big Sister’s. I did not know if she would remember me; it had been so many years ago and I was only one of her brother’s followers despite the storm I had created.

Surrounded as I was by so much pain, finally I too succumbed to waves of almost suffocating sorrow. It found expression in ritual, prayers, gongs, weeping, incense, full body prostrations in front of the formal portrait of the Grand Master who looked with unseeing eyes from behind the smoke, the chanting, and his layers and layers of robes. I threw myself down on my knees on the thin rug in front of the altar, and then down further until I was flat down on the ground, arms and legs outstretched, palms up once, twice….nine times, “Om mani padme hum….om mani….” On my feet and back to my chair.

“When did you get so superstitious?” he had once asked me teasingly .

From the smoky front of the room came talk of the Grand Master rising to heaven to take his place in the pantheon of Boddhisatvas…

Here down below I was still thinking about whether or how to make my presence known to Big Sister when someone I remembered as a sweet young teenager who helped to cook in the temple kitchen recognized me. She was now middle-aged but just as sweet as ever. She insisted on dragging me to the aisle in front where Big Sister greeted me with wonderful warmth. She pulled me down into the chair next to her and did not let go of my hands.

“He ’s suffered enough. How much can a man take? We should be happy he’s free at last. This is a cause for celebration.” Both her hands were still holding mine; her skin was dry and warm. I felt my spirits lifting. Here was an island of cool, blessed reality.

The cane was because she had had a knee replacement. She was recovering well. Her husband had died a few years ago. She still lives in the Valley in a small apartment not far from the temple where she often goes to help out. Her four kids, nicknamed East-East, South-South, West-West, North-North (she was amazed that I remembered their names) were all married…She was a grandmother. I told her I had a sixth month old great grand daughter …

As we chatted, in another part of my mind, Lin Yun, disencumbered of his earthly responsibilities, was finally making his escape, through the hole to another realm.

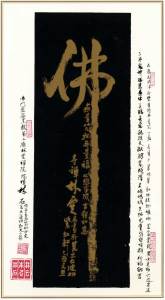

A calligraphy of “Buddha” by Lin Yun, done in 2005. In the colophon he blesses sentient beings in all six realms; animals, plants, minerals, rich or poor, honorable or dispicable, male or female, old or young; mortals from the six directions, immortals of the three worlds, smart or stupid, beautiful or ugly, benevolent or malevolent, closely related or distantly connected, friends or enemies,widower or widowed, disabled or ill, unwed mothers, orphans and minorities…He exhorts his disciples to emulate Avalokiteshavara’s perfect compassion and mercy by “fulfilling requests everywhere and offering refuge in the ocean of samsara”.